Today we had arranged to meet friends and to go on a visit somewhere, perhaps Fenton House in Hampstead. However, as it was rather cold and came on to rain, we changed our plans and decided instead to go on a local visit.

We met near King’s Cross and walked through the station on our way to our next destination. The above photo shows a deceptively quiet side of King’s Cross station. Rebuilding has been going on for years and will continue for some time yet. The site is quite a mess with new paths appearing, old ones becoming blocked and barriers springing up where least expected.

King’s Cross station is being extended and the extended portion has been roofed with this glass dome and projecting canopy that makes it resemble the popular image of a flying saucer or perhaps a giant jellyfish.

King’s Cross station and St Pancras station are separated by no more than a modest roadway. This is because when the railways were first being developed, rival companies wanted to build termini at this strategic spot. A feature of St Pancras – the London terminus of the Eurostar international railway service – is this huge sculpture on the upper level. Called The Meeting Place, it is by Paul Day and shows a man and a woman meeting in a tight embrace.

The Midland Railway intended their station to impress. A competition was held and early in 1866, the most expensive of the submissions was selected. The architect was the already famous George Gilbert Scott, working in the Gothic revival style.

After narrowly being saved from demolition by a campaign led by poet John Betjeman, the station building underwent many years of refurbishment. Today, the building accommodates prestige apartments and an upmarket hotel.

Everywhere you look there is a wealth of imaginative and creative detail to admire. I accept that nothing so intricate could be built today but how different it is from the dull and talentless design of most modern architecture. The fact that we nearly lost it to the greed and vandalism of the “developers” makes it all the more valuable.

We made our way to the British Library where we were amused by these warning signs drawing attention to the steps. In second thoughts, though, it would probably be possible to stumble as the steps are shallow and not very obvious.

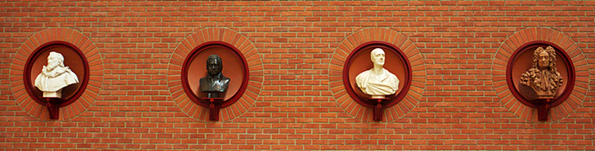

By Louis Roubiliac, bequeathed to the British Museum 1779, transferred

to the British Library 2005

What was to become the British Library was founded in the 18th century around collections contributed by a number of benefactors including King George III. What is known as the King’s Collection still forms the core of the Library, both symbolically and physically.

In the centre of the public area stands this remarkable 4-storey glass tower, discreetly illuminated, which contains the books and documents collected by George III and donated to the library. At its foot is a cafe where today people sit sipping coffee and typing on the laptop computers.

In the basement, in a dark corner, is a printing press – an appropriate piece of furniture for a library. This one is a model of an 18th century press, based on that of Benjamin Franklin. It would have been very similar, a notice tells us, to that used in 1454-5 by Johannes Gutenberg. The darkness of the alcove makes it hard to see, never mind to photograph, the press.

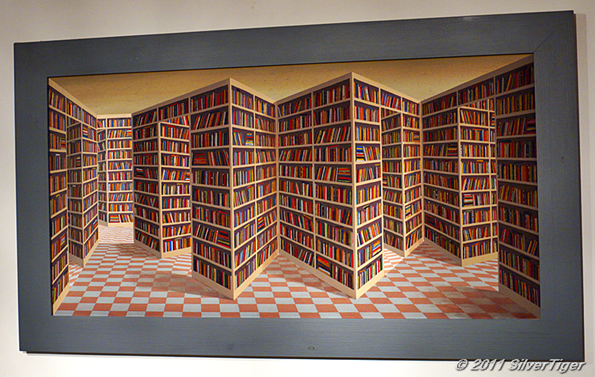

In the basement also is this picture by Patrick Hughes. Is it more than a rather dull picture of a library containing bookcases full of books? The strange title might give you pause. Then there is what happens when you look at the picture from different angles. Consider in particular the two “archways”, one near the centre of the picture and the other on the right.

When we look at the picture from the left, the left arch is narrow and the right arch is wider. What happens if we move to the right?

If we move to the right and look again, the left arch has opened and the right arch has narrowed. If we were looking at a flat picture there would be no change at all and if we were looking at a 3D model, the opposite would happen. What is going on?

This view taken from the extreme right, gives some idea of the picture’s secret. It is not flat but made with projections that create a “pseudo-3D” effect. As you move to right or left, the projections cause the picture to change but with a perspective effect that is the opposite of what you would see in a genuine room or 3D model. It is so well done that even the camera is fooled at any but the most extreme angles.

In the entrance hall or atrium is this intriguing artifact, another one that is well at home in a library. There is obviously a delicious ambiguity to it: is it a work of art or is it a bench? Or is it perhaps art for sitting on? It does get sat on and fulfils that purpose perfectly well but at the same time it is a representation of a book. But what about the chain to which the book is shackled? What is the meaning of that?

The British Library has numerous galleries and side rooms where the exhibitions take place. Photography may not be permitted in the exhibitions because of copyright issues but you are allowed to take photos without restriction in the other public areas. The building is itself quite interesting, allowing multi-level views.

The British Library is one of the UK’s six “legal deposit” libraries, which means that it receives a free copy of every book published in the UK. It is also a study library but in order to study here you need to obtain a Reader Pass for which you need to make out a good case.

There are always interesting exhibitions and displays at the British Library and an unusually large shop selling books and other more or less relevant items. It is a place that you can visit again and again, always finding something new.

After our visit to the British Library, we returned to St Pancras and the upper level where we enjoyed a late lunch in the pub there that bears the appropriate name of the Betjeman Arms.

Copyright © 2011 SilverTiger, http://tigergrowl.wordpress.com, All rights reserved.

2 comments:

One wonders why Roubiliac chose to portray Shakespeare with his waistcoat unbuttoned in the middle.

I like the book bench thingie, but I too am at a loss to ascertain the significance of the ball and chain. I do know that in medieval times, books, which were rare and valuable, were chained to the reading desks to prevent people from making off with them.

You could be right about the ball and chain being a reference to the old chained Bibles.

As for unbuttoned Shakespeare, I have no idea. Perhaps it represents the absent-minded man of letters.

Post a Comment